Underwater archaeologists from NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program identified the wrecks of two whaling ships in the Chukchi Sea this week. The two vessels were lost in the infamous 1871 whaling season, when ice floes crushed 33 ships. The diminished sea ice cover in the area, a symptom of climate change, has allowed divers to explore larger swaths of the coast.

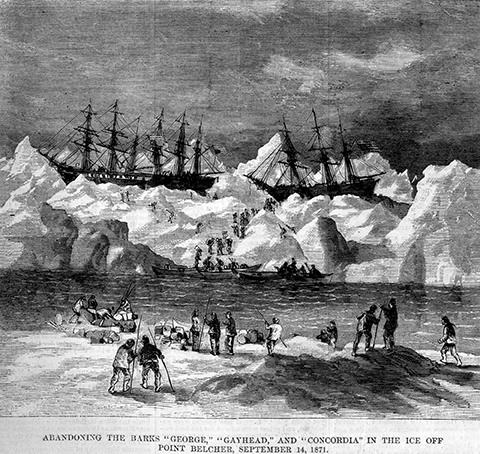

In the summer of 1871, a fleet of 40 American whaleships sailed north through the Bering Strait to the Chukchi Sea to hunt bowhead whales. They reached as far as present-day Wainwright, Alaska, by August, where the captains waited for the pack ice to clear so they could venture into the open ocean. Instead of shifting from the east as it had always done in years past, the winds pushed the floes toward the ships, pinning them against the coastal shallows.

Seven ships escaped the squeeze, but 33 remained trapped. By September, the captains and more than 1,200 crewmembers had abandoned the fleet. Ice demolished them within weeks. The refugees piled the whaleboats with provisions for three months and sailed 70 miles to the south, where the seven remaining ships rescued all hands. To fit everyone aboard, however, the ships abandoned their hard-won oil and whalebone, which the historian Alexander Starbuck estimated to be worth more than $30 million in today’s dollars. The disaster contributed to the demise of the American whaling industry in Arctic waters.

Exactly 144 years later, NOAA researchers probed a 30-mile stretch of Chukchi Sea coastline near Wainwright, Alaska. They found evidence, discovered by previous dive teams, of gear salvaged by the Inupiat locals and timbers from ships’ hulls. The objects suggested that the rest of the ships still lay on the seabed. The artifacts located this year included the two identifiable wrecks as well as anchors and brick try-pots.

“Until now, no one had found definitive proof of any of the lost fleet beneath the water. This exploration provides an opportunity to write the last chapter of this important story of American maritime heritage and also bear witness to some of the impacts of a warming climate on the region’s environmental and cultural landscape, including diminishing sea ice and melting permafrost,” said Brad Barr, NOAA archaeologist and project co-director, in a statement.

The search for the abandoned whaling fleet was funded by NOAA’s Office of Exploration and Research, in collaboration with the NOAA Office of Coast Survey and the Alaska Region of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.