Just-published report reveals that oil and gas and shipping activity is on collision course with whale habitat

The World Wildlife Fund (Canada) has published a paper in the journal Marine Policy that reveals the extensive overlap of areas targeted for Arctic energy development with the habitat of the endangered bowhead whale.

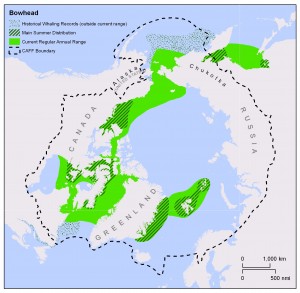

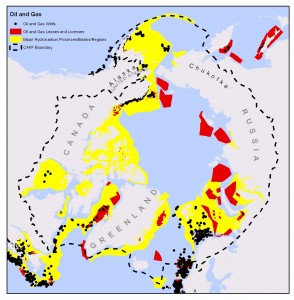

Reported by the Iqaluit, Nunavut-based newspaper Nunatsiaq News, the WWF collected data from conservation experts around the world to map the habitat of the year-round Arctic whale species—bowheads, belugas and narwhals. They also collected the latest information about cetacean hang-outs during the Arctic summer, when oil and gas exploration is at its peak. The report shows how some planned and existing oil and gas and shipping projects overlap the places important to the whales’ future survival.

“These ice-adapted Arctic whales are already stressed by rapid climate change,” noted Pete Ewins, an author on the paper and Arctic whale specialist for the WWF. “Killer whales are moving into their territory and preying on them, their food sources are moving, and now on top of that, industry is on their doorstep.”

Off the coast of Nunavut, for example, major hydrocarbon deposits are believed to lie beneath the Baffin Basin. Ewins told Nunatsiaq News that 60 percent of local whale habitat overlaps with energy exploration areas. “Oil and gas exploration is risky business—it’s good for the economy, but it’s bad for the whales,” Ewins added. We have to plan wisely” for energy development in the polar regions.

Besides revealing the alarming proximity of whale habitats to theorized hydrocarbon reserves, the report suggests how conflicts can be reduced in an Arctic with decreasing sea ice cover. The risks of oil spills in icy waters are highlighted as the biggest and most difficult risks to manage or avoid. Other side effects of oil and gas drilling affect cetaceans in particular. Ship strikes are a major problem, as is seismic testing and other underwater noise. And these man-made dangers are just the cherry on the climate change cake.

The WWF offers suggestions for mitigating the harm to struggling whale species while acknowledging the global interest in drilling for oil and natural gas in the frozen zone.

“It’s not only about declaring the most important places”—where whales calve, rear young, rest and feed—“off-limits,” says Ewins. “For instance, in some cases, simply slowing ships when they’re entering these highly sensitive areas could be enough to reduce impacts. In other cases, the whales are only using these areas for a specified time, so it should be possible to just avoid those areas for that period.” The paper also argues for better monitoring of the whales’ responses to disturbance, in order to determine their precise sensitivity to different forms of human activities.