A current exhibit—that I wish I could see for myself—at the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Wa. explores my favorite subject: the intersection of art, polar science and the history of exploration. Vanishing Ice: Alpine and Polar Landscapes in Art, 1775-2012, is on view through March 2.

“First and foremost, this show is a tribute to the beauty and majesty of ice and its influence on the history of art, science, literature and exploration,” said the museum’s executive director, Patricia Leach, in a press release.

Ice was introduced to the British scientific establishment by William Scoresby. His first major paper, On the Greenland or Polar Ice, was read in three parts before the Wernerian Natural History Society in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1814-1815. The paper, the first scientific analysis of polar ice, describes the appearance and behaviors of glaciers, bergs, floes, fields and other formations from an oceanographic standpoint.

These were no mere cubes clinking in a cocktail glass. This ice was immense, beautiful and malevolent, seductive and dangerous:

“Of the inanimate productions of Greenland, none perhaps excites so much interest and astonishment in a stranger, as the ice in its great abundance and variety. The stupendous masses, known by the name of Ice-Islands, Floating Mountains, or Icebergs, common to Davis’ Straits and sometimes met with here, from their height, various forms, and the depth of water in which they ground, are calculated to strike the beholder with wonder: yet the fields of ice, more peculiar to Greenland, are not less astonishing. Their deficiency in elevation is sufficiently compensated by their amazing extent of surface. Some of them have been observed near a hundred miles in length, and more than half of that breadth; each consisting of a single sheet of ice, having its surface raised in general four or six feet above the level of the water, and its base depressed to the depth of near twenty feet beneath,” he wrote.

Scoresby wrote from experience, having spent more than 10 summers whale-fishing in the Greenland Sea. At one point in the narrative he demonstrates the brutal energy of the ice and ocean currents:

“In the year 1804, I had a good opportunity of witnessing the effects produced by the lesser masses in motion. Passing between two fields of bay-ice, about a foot in thickness, they were observed rapidly to approach each other, and before our ship could pass the strait, they met with a velocity of three or four miles per hour: the one overlaid the other, and presently covered many acres of the surface. The ship proving an obstacle to the course of the ice, it squeezed up on both sides, shaking her in a dreadful manner, and producing a loud grinding, or lengthened acute tremulous noise, accordingly as the degree of pressure was diminished or increased, until it had risen as high as the deck. After about two hours, the velocity was diminished to a state of rest; and soon afterwards, the two sheets of ice receded from each other, nearly as rapidly as they had before advanced. The ship, in this case, did not receive any injury, but had the ice been only half a foot thicker, she would probably have been wrecked.”

Scoresby may have dazzled the Wernerians, but none of his drawings of Spitsbergen’s glaciers or bergs is included in Vanishing Ice. Many of his contemporaries are accounted for, however. One is Sir John Ross, who led the British Admiralty’s first voyage of discovery to the Northwest Passage in 1818—a command Scoresby dearly sought for himself. Ross’ 1835 watercolor drawing, Snow Cottages of the Boothians, depicts the band of friendly Inuit who wintered with Ross’ 1829-1833 voyage to the Arctic. Against a snow-covered outcropping framed by a star-studded night sky, figures in fur suits gather before a cluster of igloos. One figure in a blue jacket and trousers appears to be speaking to the group with hand signals. The scene probably illustrates the “Boothians,” native Canadians living on the Boothia peninsula, who supplied the explorers with fresh meat.

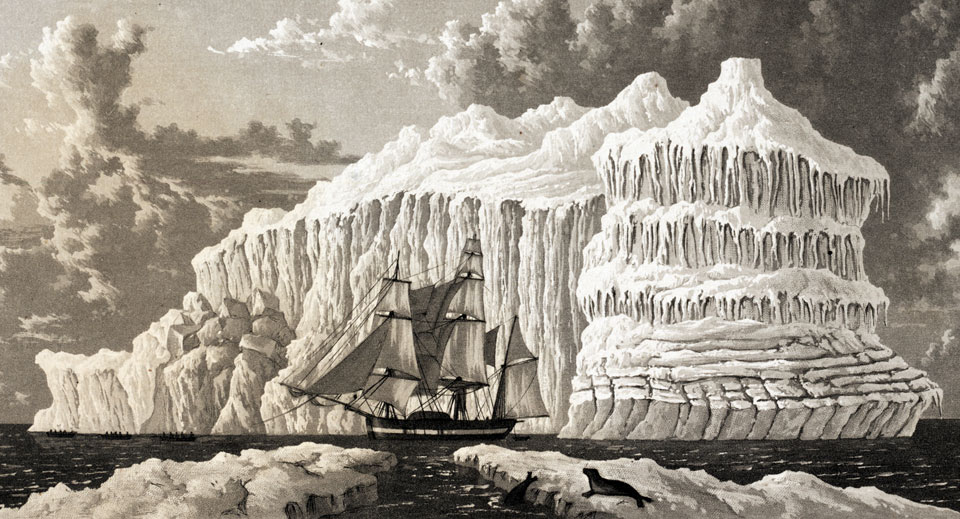

Frederick William Beechey, another of Scoresby’s contemporaries, was a naval officer on William Edward Parry’s second Arctic voyage in 1819-1820. His HMS Hecla in Baffin Bay, a pencil drawing published in Parry’s Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a Northwest Passage, 1819–20 in His Majesty’s Ships Hecla and Griper, depicts the expedition’s lead ship against a monster iceberg resembling a tiered wedding cake. A seal perched on a floe keeps an eye on the vessel, while the sky is lit with cumulus clouds.

More complex works from the second half of the nineteenth century build on the eyewitness accounts of the early explorers. William Bradford’s 1867 painting, Caught in the Ice Floes, reveals the motion of the ice pack as it encircles a helpless ship. A sealing crew in the foreground unloads the ship’s smaller boats onto tenuous islands of ice. The drama is heightened by the play of light on the sky, a central iceberg and the dark sea between the floes.

Vivid illumination captures the Romantic excitement of the polar regions in paintings by Hudson River School artist Frederic Edwin Church, Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner, just to name a few in this fascinating exhibit.

Vanishing Ice also weaves the theme of climate change into the display. The curators highlight the impact of the polar regions on art and science over the past two centuries, and suggest that we still have a lot to learn from the Arctic and Antarctic. And that time is running out.