Was the Franklin Expedition doomed by its badly canned food? Or did the men succumb to a combination of unfortunate factors? A new study asserts that all 129 British sailors on the fated expedition died from a “marvelously catastrophic” mix of causes—and lead poisoning was just one of them.

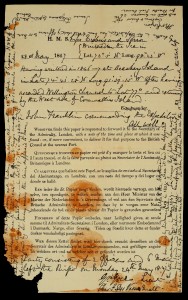

Professors Keith Millar and Adrian Bowman of the University of Glasgow and William Battersby of London examined the much-studied remains of three crew members who died just six months into the voyage, whose mission was to explore the last unknown portion of the Northwest Passage. William Braine, John Torrington and John Hartnell were buried on Beechey Island in the Canadian Arctic when the expedition wintered over in 1845-1846. That September, after exploring Wellington Channel and Cornwallis Island, the expedition ships Erebus and Terror were beset in Peel Sound west of King William Island. They expected to be freed in spring when the ice broke up. Lieutenant Graham Gore left a note in a cairn on May 28, 1847, indicating “all well.”

Their commander, Sir John Franklin, died two weeks later. The ships remained stuck. The crew deserted them on April 25, 1848, and eventually perished on a fatal march toward the Great Fish River. Scientists are still trying to figure out why.

The new study, published last month in the journal Polar Record, reevaluated the theory first advanced by anthropologists Owen Beattie and John Geiger in 1990. In examining the bones of 18 of Franklin’s men, Beattie and Geiger found unusually high levels of lead, prompting them to conclude that expedition was felled by lead poisoning from poorly-sealed canned foods.

Millar, Bowman and Battersby extrapolated Beattie’s and Geiger’s findings and estimated whether the entire crew would have experienced lead poisoning. They concluded that some, but not all, would have become seriously ill.

“What is absolutely clear is many of them had high levels of lead. What is less clear is if that was unusual given their background in highly lead-polluted Britain. And the variation across the men that we’ve estimated shows they may not have been affected at all,” Millar told Canada’s CBC News.

“In Britain in the 19th century, lead poisoning was not uncommon,” Millar added in an interview with The Globe and Mail. “Water was often provided through lead pipes, from lead storage tanks, there was a lot of atmospheric lead, there was a lot of lead in food and so on. So the fact that high levels of lead were found in these sailors in the Arctic, we don’t know whether that would have been any different to lead in the British population as a whole.”

Instead, Millar and his colleagues suggest the men suffered from incredibly bad luck. Their food was of poor quality and lacked Vitamin C, which caused scurvy. Their commander died from a still-unknown cause. The expedition took place during an Arctic cold snap, in which the ice failed to clear Peel Sound for at least two years.

John Geiger, who personally examined the lead solder from cans at various Franklin sites in Nunavut, maintains that the contaminated food would have been harmful. But he also agrees with Millar et al. “There has never been any doubt in my mind that it was a combination of factors, of which lead was one,” he told The Globe and Mail.